This week had its share of scandal. Tannhäuser in Düsseldorf was literally booed off the stage. What can be known for sure is that the production by Burkhard C. Kosminski focused on Nazis, concentration camps and had depictions of "graphic" violence. No one on the American opera lists had seen the production but of course condemnation was fast and furious. Defenders were operating on the principal that what is called Eurotrash in Amercia, and in Europe,Regie Theater is better than the prettified Classics Comics approach of Otto Shenck, who did the empty and obvious production at the Met. However, without seeing what Kosminski actually did, it's hard to know if this was just unpleasantly provocative; and defending it seemed pointless. Burkhard C. Kosminski was out of a job, regardless; his production was cancelled.

The ghastly Ring Cycles at the Met ended and so did the ghastly Ring. It's been widely reported "the machine" won't be back and it may well be seven to ten years before the house tries the Ring again. "The machine" was symptomatic of the tech/TV/movie culture we live in. This is a catastrophe for Peter Gelb, dictator of the Met, because it betrays his naive, superficial and amateurish nature. A pro, looking at the sketches, the plans, and hearing the utterly disastrous director Lepage talk would have seen this for a ruinously expensive loser. But Gelb wanted The Transformers Ring. As in those movies, all that had to happen was "special effects". The mentally disabled attracted to such movies demand nothing else. How ridiculous of Gelb to assume that such people would want to sit through the hours Wagner's Ring requires. Musically this was a bad showing. There were a few good singers, but too many of the crucial roles were poorly to badly sung. And for my personal taste, the conductor, Fabio Luisi, still has a lot to prove beyond a certain technical proficiency.

But, this week, I thought I would republish something I wrote for a toilet rag fourteen years ago. It's a tiny part of history now, as much has changed. But I hope those who didn't read it the first time might enjoy this, as one enjoys "non-fiction" from years ago. It's very long in the Internet Age even though I've cut quite a bit but I hope some of this experience remains, it was a great joy for me. It's in two parts. Part two will run next week.

THE WIDDER HAINTS LA SCALA IN 1999

Riccardo Muti saved me from the Gypsies. We were in Milan, on an unusually warm day for February, walking to lunch on my first day at La Scala. "Where is your overcoat?" he asked. "Walk along in just a sweater, and suddenly little people will surround you. Gypsies. They will cover you with a rolled-up newspaper." He shapes both hands around an imaginary paper and conducts them over me, a mesmerizing presto in 6/8 time. "They will then vanish, and so will your money, and your watch and anything else they can get. You be careful."

Sure enough, a few days later I was walking to rehearsal when, on a crowded street corner, with carabinieri watching, I was circled like a flame by a gang of young women -- human moths, carrying newspapers. They were swift, silent and sudden. "Via!" I yelled, hitting at them. They scattered. There was applause. I looked sharply over at the cops, who merely shrugged.

I wasn't so unnerved by the thought of having nearly lost my money and passport- but the Gypsies would have gotten my pass to La Scala! It had been stamped just a few days before by the company's sovrintendente (the big boss), Carlo Fontana.

"You see, I told you," Muti laughed later. "Always have armor on when you walk in the world. The Gypsies may still get you, but they will have to work for what they get."

I was at La Scala in spring 1999, to cover the final weeks of rehearsals and the first two performances of a new production of La Forza del Destino - the first time La Scala had mounted the opera in twenty-one years. (The cast back then offered Montserrat Caballe, Jose Carreras, Piero Cappuccilli and Nicolai Ghiaurov.)

Oddly enough, many of the concerns about La Scala and by extension opera in Italy, were not merely local or national. Fourteen years later, I see that we were just at the beginning of serious problems for the form everywhere. What might be the disease that will kill opera, or change it radically, was manifesting itself in a crazy country called Italy and at a theater that symbolized the form at its height.

Changes would occur at La Scala – as of 2013, the great old theater has been rebuilt and modernized at Muti's urging. The certainty that nothing could possibly happen in Italy on schedule without graft would be disproven. After overseeing this, giving opera in the suburbs for a few seasons, raising money as needed, deciding on issues that affect the acoustics of the house and the functioning of the stage and doing away with the notorious “loggione” mentioned often in this article, Muti was thrown out and replaced in 2005. But La Scala, though apparently efficiently run today no longer has the “sacred fire” hovering about its name. It’s just another prominent European theater, with all the problems that effect opera everywhere. Once the pinnacle of a career for the greatest Italian singers, there are very few Italian singers any more. La Scala competes for the same ten or so big names that draw enthusiasm everywhere, and loses as often as it wins in engaging these people.

Back in 1999, there was a sense that Scala had become less important, chaotically managed, ungrateful for singers and no longer a key to international superstardom.

Riccardo Muti was at the center of much of the controversy surrounding La Scala. Though a world famous conductor (and one of the most highly regarded conductors in the world today) opera lovers in particular tended to dislike what they thought they knew about Muti; he was not popular with some important singers. Before coming to Milan even I hadn't been sure about Muti. Already he was starting to win me over. I admitted as much to Elvio Giudici, a leading critic of La Musica and contributor to La Repubblica. "But of course," Giudici snapped, "Muti is buying you!" Then he hung up on me.

Like all the big institutions in Italy, La Scala has a hierarchical structure and a feudal feel. Three people were in official positions of power (the positions remains, but those people have gone). First is the sovrintendente, "Dottore" Carlo Fontana. Then there is Maestro Riccardo Muti, direttore musicale, followed by Maestro Paolo Arca, direttore artistico. (Muti tells me it is Italian law that the artistic director of any theater must be a "maestro," a musician with credentials. Orchestras have been known to strike if they felt the artistic director was not a good enough musician -- whether he conducted or not.)

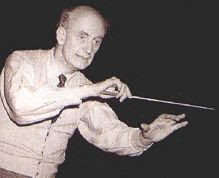

(Muti, younger and older)

Muti was the world's most publicly detested conductor. In her "book"Cinderella and Company, Manuela Hoelterhoff calls him "the famously short maestro of fear." Now, we know that Hoelterhoff is an idiot, as indeed are most people who comment on the arts – ALL the arts in America. Hoelterhoff has no training, no knowledge, no experience in art, only the shark's ability to sell herself as someone who knows about an art form few people know or care anything about. Things had already gotten really bad in 1999, but by 2013, any locus of critical responsibility has collapsed in America.

Eying the conductor in New York in 1998, a far more knowledgeable person remarks, "you just get younger looking." This is Itzhak Perlman, when he comes backstage after a grueling Vienna Philharmonic concert at which Muti has led the Schumann Second and the Shostakovitch Fifth. "Oh, caro, no," says Muti, "it is all a trick. You know - the hair dye." In a second, Muti becomes a hairdresser dumping a ton of polish on his head and wiping it in. "And then of course, there is the plastic surgery." Instantly, he shifts from hairdresser to surgeon, staring at his features in the dressing-room mirror, then pulling his face in forty different directions in thirty seconds. Everyone laughs except Perlman, who continues to peer at him. “You are very funny, Maestro,” says Perlman, "tough funny.”

In Milan, Muti says to me, "I am not La Scala. Carlo Fontana is the boss. He consults with me, of course. But the final decisions are his." In 2005, Muti fired Fontana as part of a power play. The Opera House went on strike in favor of Fontana. Muti prevailed short term but was forced out. Muti is adored worldwide, received the million dollar Birgit Nilsson Prize, heads the Chicago Symphony and even had a triumph at the Met, with Verdi's Attila. What's Carlo Fontana been up to? For that matter, what is to be said about Hoelterhoff? Part of the fecal mass that works for Bloomberg, she will die, meaningless and forgotten. Muti hasn't viewed his career as a popularity contest. No one who has ever had a great career has.

A case can be built against Muti's taste and tactics. But his talent? At a thrilling New York Philharmonic concert of Ravel, Busoni and Brahms in January 1999 (at which the orchestra refused to bow, applauding the maestro instead), the stunning Vienna Philharmonic concerts in New York in March, the Forza orchestra rehearsals, his ear, insight and authority were remarkable.

Muti ascended the throne in 1986. One of the musicians who, out of "human kindness," tried to help with the transition, bristles at the suggestion that the rot set in at least a little while before Muti arrived. "Ma, no!" he yells deafeningly. "This Abbado - I mean the giant, Claudio - he not nice man, but he great visionary of the theater. La Scala now is a disaster. And there is one cause Muti, Muti, Muti. I work with him. I know. Basta."

Cautiously, I bring this point up with Muti. He is surprisingly sweet about it. "That is La Scala. They crucify you while you're here and canonize you later. Now, Maestro Abbado is a saint. I will be a saint too, once they do me in."

Hatred of La Scala in '99, and of Muti, was far from muted. The angry feelings of malcontents were vented in the alternative press and in the second most feared place at La Scala the top gallery, or Loggione. The most feared place, of course, is the Sala Gialla.

The Sala Gialla, (“the yellow room”) a windowless chamber in a corner of the second floor of La Scala, was where Toscanini rehearsed. After his time, the Board took it over. They still meet there. But Muti reclaimed it for his rehearsals. It's a long, forbidding room with a massive table in the center. On the walls are pictures of the wreckage of the house after the allied air raids during World War II. Above the grand piano at the far end is a huge, terrifying portrait of Arturo Toscanini. He glares down at everybody who enters the room.

"I call it the Muti diet," says Lauren Flanigan. "You get a contract at La Scala, and you expect to sing. You show up, and there are three other people cast in the same role. You lose a lot of weight obsessing about if and when he'll pick you." Flanigan remembers her experiences rehearsing the role of Abigaille in Nabucco for Muti. "There were four of us Abigailles. Three of us got to be friends. The fourth we called `the nuclear Abigaille' -- we figured she was there in case the rest of us got killed in a nuclear holocaust, they'd have her. She was like a roach; she'd live through anything. So the scene is going on, and he points from one person to another with his glasses, and you have to be ready to get up and sing. If he catches you by surprise and you choke, he gestures to somebody else, and you think, `I'll never get it now.' So I learned to push my way to the head of the table, so I could see the glasses coming in my direction. I came back thirty one pounds lighter."

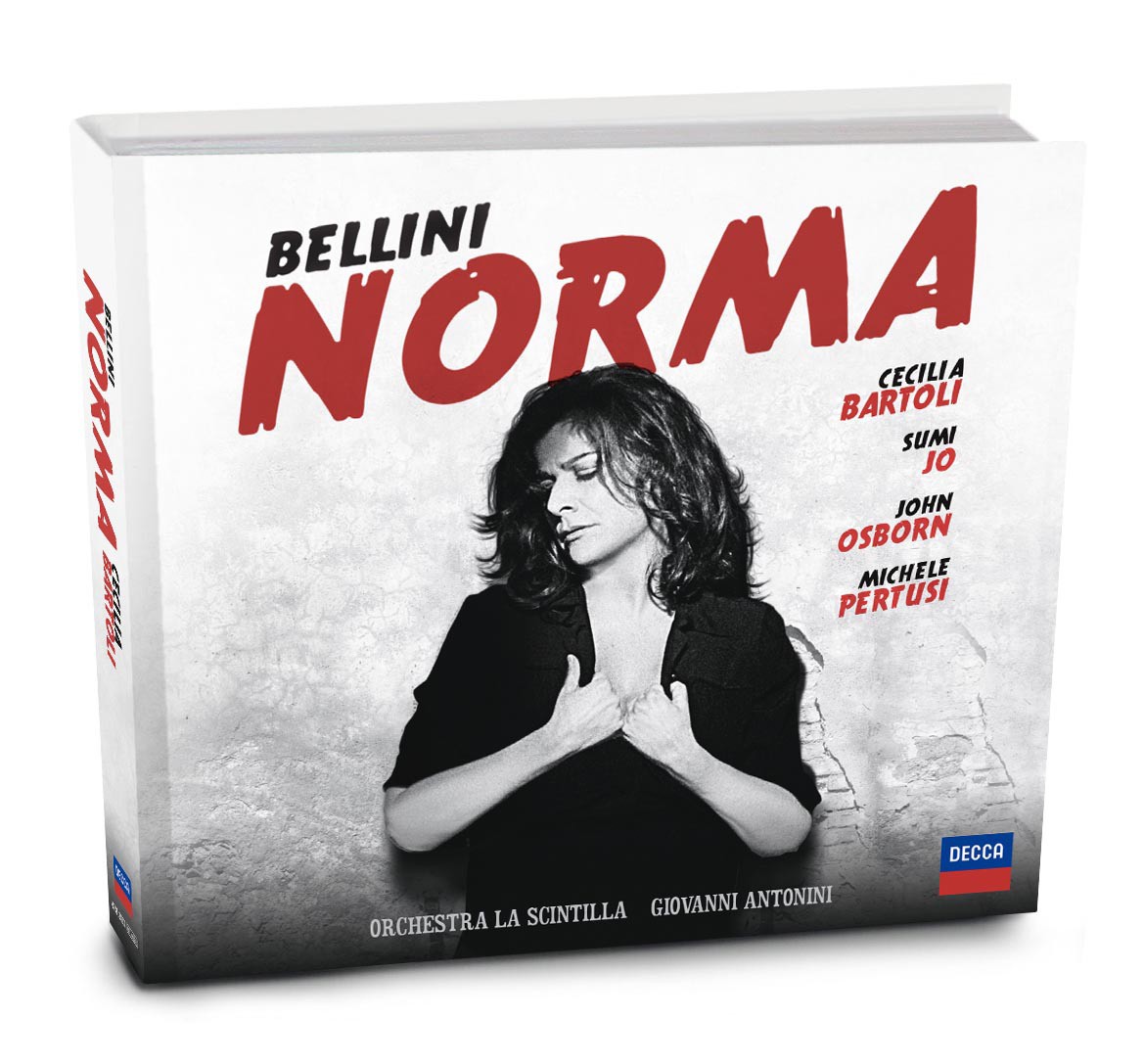

The Sala Gialla is where Cecilia Bartoli met Renee Fleming. "Muti's yellow room, it is like Scarpia's torture chamber," Bartoli said back then. "Everybody is there, and he goes back and forth. My cover was always there. Muti keeps people in the dark. No one ever knows who will actually sing.""Rehearsing was like having high-school sing-offs," adds Fleming- "You sing it now, then you sing it.' That's… trying!"

On my first day Muti sees me in the Lobby. "These are our guards and our Gods," Muti says, pointing to the giant statues of Rossini, Verdi, Donizetti and Bellini. He opens the gold-framed glass doors and guides me into the shadowy theater. "This is our church."

We both look in silence for ten minutes. He vanishes, and I sit in this space, trying not to feel overwhelmed by sentiment. There are the gorgeous gilded boxes, glinting down on the plush red seats. Up there is that amazing chandelier, and above it the ceiling, with its intricate patterns suspended by magic in thin air. And then, the stage. Even with the curtain up and workmen on platforms and ladders, it is breathtaking. The rehearsal lights are unlike any I've seen elsewhere. Mysterious figures emerge, then sink into semidarkness. My eyes are tricked into seeing haunted poses, my ears into hearing fluttering sounds. There are only stagehands moving scenery. The auditorium was merely fifty-three years old in 1999; the stage goes back much further. But time evaporates in here. An art form, maybe one that is vanishing, is made flesh, so to speak. One can reach out and almost touch -- one fears -- the diminishing mist of something that is disappearing.

La Scala was completed in 1778, on the site where the church of Santa Maria della Scala once stood. The theater was run by a group of noble families, who hired impresarios to organize seasons, until 1815 - the year La Scala began its ascendancy. As part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Milan and its primary theater enjoyed large subsidies. It became a showplace for the powerful Austrian government officials stationed in Milan. In 1859, when Italy was united (though how united the country actually became is a matter of serious and continuing debate), Milan's emerged as the jewel in the crown of Italian opera houses, even though the government was centered in Rome.

The Milan of 1839 was a paradoxical place that was typically Italian - famous, but insulated and provincial. Many of the intellectual Milanese say the same thing about the city today. Regional antagonisms were inevitable. One reason Verdi was denied entry to the city's Conservatory was that he was a foreigner! Most Italians are still foreigners to the Milanese. Southern Italians are despised by the locals. They are called terroni, a word with nasty connotations. The idea is that the North (and Milan is the great city in the North) pays all the taxes squandered by the bums down South.

Claudio Abbado, Muti's predecessor, is from a great Milanese family - an elegant, intellectual Northerner. Muti is from the far South. He was born in Naples (his mother drove all night so he would be born there) and raised in Naples. Arca is from Rome. Tirola has Neapolitan ancestors. Maestro Montanari, the "conductor of the stage," is Neapolitan through and through.

Muti invites me to a birthday party for Montanari, a longtime collaborator. Italians are more sensitive to accents and regionalisms than the English, and every bit as snobbish. Usually, my Italian accent inspires a lot of sniffing, if not confusion -- especially when I'm nervous. ("Please speak English," is asked of me often at La Scala.) I'm more relaxed chatting with them in this context, and suddenly they all stop. Muti takes a long time squinting at me and says, "Those vowels - I notice -- Provincia di Chieti?"

"Well, Maestro, my paternal grandfather was from there." There is another silence. "Then you are one of us," cries Muti - and my grandfather and I are toasted. "Yes, I suppose we are terroni," says Muti. "But what does that word come from, after all? Terra - the earth. Italy and art and all of us are of the earth, where else are we from? The great soil of Italy. If they think that is an insult they are maleducatevi- ignoramuses."

Verdi gradually helped make La Scala a great house artistically on the international scene. In a sense, it was his Bayreuth. There he had his first big hit, Nabucco, and his worst failure, Un Giorno di Regno. His relations with La Scala were often strained. But the glorious world premieres of the revision of Simon Boccanegra, Otello and Falstaff carried immense prestige and glamour over into this century.

In 1897 came a "period of austerity," when subsidies were cut off. Those were crisis years. Eventually, a way was found to secure the house by obtaining more private funding and operating more like a corporation. Publisher Giulio Ricordi, along with composer, librettist and artistic propagandist Arrigo Boito, used La Scala to dominate art in Italy. They had help from the many wealthy and powerful families in Milan, such as the Visconti. Then as now, Milan was the business center of Italy. These powerful industrialists, politicians and intellectuals saw La Scala as their opera house.

While Puccini had as many flops as hits at the house, and La Fanciulla del West and II Trittico had their premieres at the Met, La Scala was crucial to him and to all the other Italian opera composers of his time and later. It also helped establish the international viability of operas by Richard Wagner, Richard Strauss and Claude Debussy, most of these thanks to Arturo Toscanini, who had two terms running the house and was the first of a number of powerful conductors to have varying periods of control. Toward the end of World War II, allied bombs hit the theater, destroying the auditorium. "We wish it had been the other way around," says Arca, sighing. "If only your American bombs had hit the stage! Instead, they had to rebuild the auditorium. They kept the stage, which was absolutely undamaged. That was a disaster. Now we must rebuild the stage, which is too old fashioned."

In the 1930s and '40s, the great conductor Victor De Sabata held sway at La Scala. After he became sick and lost interest in the early '50s, Antonio Ghiringhelli, an upper-class Milanese businessman/bureaucrat, took over. Though he feuded, Italian style, with all of them, Callas, Tebaldi, Visconti, the young Zeffirelli and a host of world-renowned singers had important seasons at the house. In the 1970s, Claudio Abbado made a significant artistic contribution with acclaimed Giorgio Strehler productions of Macbeth and Simon Boccanegra Abbado also had access to a diminishing but impressive roster of artists including Mirella Freni, Shirley Verrett and Piero Cappuccilli.

Starting in the late 1980’s the house’s luck in creating stars began to run out though Roberto Alagna -- then a hot property -- was a Muti discovery. Pavarotti, Freni, Scotto, Cossotto, Cappuccilli, Ghiaurov, Bruson, Bergonzi, stars of an earlier La Scala era, some still active at the time, were all over sixty in 1999; Simionato, Tebaldi, Corelli, Gencer, Stella, Di Stefano, Guelfi, Taddei were retired. Del Monaco was deceased. All of these were what the Italians call "creatures of La Scala" for longer or shorter periods of time. In 2013, most of these great singers have died.

Aside from Alagna, none of the big names in the international opera world under fifty owes anything to La Scala, and Muti is unique in being the only conductor to run the house and not produce international stars. "I know that," he says. "It is always in my thoughts. But give me names - any names from anywhere in the world. We are doing the Verdi Centennial. I need names for Ballo, for Otello. You tell me, you tell Arca, you tell Fontana. We will pick up the phone that second and try for them. Give me names!" (Again, with hindsight one can see that great singers with the tremendous command and distinctiveness in the standard repertory have dried up; fourteen or so years later one is hard pressed to find imposing voices and great personalities anywhere).

Returning to Forza, the most certain element, besides Muti, is the conservative Argentinean regisseur, Hugo De Ana. He is in charge of everything visual - as he was for the infamous Lucrezia Borgia in the summer of 1998 -- infamous because, during the first performance, Renee Fleming, singing the title role, was hooted, jeered, booed and finally verbally abused by a loud if not large segment of the audience.

It struck many as suspicious that Fleming was booed after she had had a well-publicized altercation with Muti over her inclusion in that ill-fated Don Giovanni. She also had difficulties over cadenzas with the conductor of the Lucrezia, Gianluigi Gelmetti, who fainted immediately following her first aria, returned after forty minutes to conduct the rest of the performance, fainted again and was rushed to the hospital.

The Lucrezia scandal was the first thing Muti talked about when we met backstage at that New York Philharmonic concert two weeks before I left for Milan. "I was in the house for two days during Lucrezia," said Muti. "I admire Fleming." I ask him about Gelmetti falling over. He ponders. “Well, I can see falling over once, we've all been tempted to do that. But twice? Strange.”

"We have a difficult public," allows Muti about the Fleming incident. When he leads me to his office on my first day in town, we pass twelve huge photos of famous maestros who have conducted at the theater, among them Carlos Kleiber, Lorin Maazel, Claudio Abbado, Karl Bohm and Herbert von Karajan. "All have been booed," Muti remarks offhandedly, "except this one." He stops in front of a portrait of Guido Cantelli, who was appointed principal conductor at La Scala in 1957. "He was lucky. He died." (Cantelli was killed in a plane crash just after his appointment was announced.)

(The two Leonoras, Ines Salazar and Georgina Lukacs)

Forza was to star the hot young Argentinean tenor, Jose Cura. It seems likely that mezzo Luciana D'Intino will sing Preziosilla. The rest of the cast for the upcoming first night, including the Leonora, is anybody's guess. Argentinean Ines Salazar and Hungarian Georgina Lukacs had been engaged for Leonora; Leo Nucci and Giorgio Zancanaro has been engaged for Don Carlo, Giacomo Prestia and Antonio Papi are two possible Guardianos. Either Alfonso Antoniozzi or Roberto de Candia might sing Melitone.

(Cura, top, and Lictira, then very impressive, close to what they looked like in 1999)

"You are the first outsider to be allowed to see this much," remarked Carlo Fontana, with big eyes and what is known in Italian as "intenzione," when he stamped my pass. "I am giving you two weeks' freedom of the theater. You can go anywhere and talk to anyone." During one very tense rehearsal in the theater, Fontanaloudly laments my presence, clasping his hands and imploring God's mercy, just as my grandmother used to do. She had an excuse -- she was Neapolitan. Fontana is a Milanese aristocrat.

"Well, that's what Forza will do to you," remarks a small but formidable lady with high, jet-black hair and rather a ferocious cast about the eyes. She's been watching what Hollywood would call the "suits" - Fontana and henchmen in Armani finery hovering around the "talent" - Muti in a sweater and a funk. She nods toward the little group, where much eye-rolling and hand-clasping is going on. Maestro's voice is soft, but his eyes are drilling small, lethal holes into his associates.

The ageless lady cackles. She is retired Turkish diva Leyla Gencer, who runs La Scala's school (roughly analagous to the Met's Young Artist program) at Muti's invitation and comes to all the rehearsals. "How is your health?" she asks. I feel fine. "You won't for long," she says. "You will have a bad influenza before Forza is finished with you. We will all be desperately sick. Wait and mark my words! Now, while they mourn, let me sit with you and tell you about my Forzas!" "Her" Forzas were fascinating. And about the influenza? She was right.

Thanks to my insider's pass, I am set to attend a 10 A.M.rehearsal in the dreaded Sala Gialla. Muti himself plays every piano rehearsal. The head coach for the production (Massimilliano Bulo in this case) stands beside him making notes for individual coachings, though Muti plays those, too, when he has time. The atmosphere is tense. Today, Ines Salazar, officially the first Leonora, will sing. She's been sick but also has shown signs of vocal distress unrelated to her ailment. She is a voluptuous, doe-eyed beauty with a face of great sweetness and a terrified air.

Georgina Lukacs, who was hired as her "cover," has sung most of the rehearsals. She's exhausted and rather grim. People are happy and hopeful about Salazar's presence. Jose Cura is in Paris, singing a long run of Carmen. "In the old days, we would not have tolerated this," says one of the artistic staff. "Cura doesn't really know this part. And this is La Scala. But he runs from here to there. Even Muti has to endure it."

Giacomo Prestia, the official first Guardiano, is sick. Leo Nucci, whom Muti wants to sing Don Carlo, is having a last minute angioplasty -- today. Muti went to see him before he went under anesthesia. No one knows whether he will be in the production. Luciana D'Intino and her second, Mariana Pentcheva, are sick. Both Melitones have a serious case of the flu. I keep thinking of Leyla Gencer's prediction.

Since Salazar is nervous, Muti asks everybody to wait outside while he works with her on her first aria. People pace. More mucus than tone can be heard from inside the Sala, even over the nervous warming up that has recommenced in the rest rooms.

When we are readmitted, Muti works through the inn scene. He is gentle with Salazar: "Is it O.K if we try that again? I don't want to tire you. You don't need to sing out. I know you have a beautiful voice." With the others, he makes jokes. He loves to get up and imitate the characters walking - a mixture of Monty Python's Ministry of Funny Walks and, when he wants to make a point, Charlie Chaplin. It's precisely observed but hilariously exaggerated.

Muti's piano playing is thrilling. He's one of those conductors who "orchestrate" at the piano, giving a clear sense of the sonority he will achieve in the pit, imitating certain instrumental combinations: "Here is the flute with the oboe - use that color in your voice"; "Here is the bassoon - let it lead you to the expression." The most intricate figurations roll out from his fingers, in tempo, with absolute precision and beautiful tone. Unlike most rehearsal players (even most conductors, when they deign to play) he is not a piano-basher but a virtuoso making music. Everything he does has an expressive purpose.

He's leading without seeming to do so - but singers are singers. There's a lot of throat-clearing, daydreaming and watch checking. They don't seem to absorb what he plays for them, even when he points out how hearing the orchestra clearly will help them project their voices.

He works intensely with Giorgio Zancanaro, who will double Nucci and may sing the first night. Zancanaro has recorded the role with Muti and sung it frequently. But he's forgotten it. Muti goes over and over various sections, just for rhythms and the right notes.

"Now, Giorgio," he says at one point, "tell me, don't you make a lot of records?"

"But certainly, Maestro."

"But you don't like to listen to yourself?"

"No, Maestro, I am proud of my records."

"Except one, Giorgio."

"Well, maybe one or two, Maestro."

"I'm thinking of one in particular."

"I was hoarse at that one, Maestro."

"No, I mean our Forza"

"Did we record Forza, Maestro?" There is a pause. "I think I lost that, Maestro. I will buy it today." Muti finds this hilarious, but Montanari, the maestro of the stage, rolls his eyes.

Muti works with everyone on the words and the precise expression of every moment. He is also looking for what American acting teachers and stage directors call the "arc" of the character. With Zancanaro, he tries to get at the unstable nature of Carlo - a good-natured, clever storyteller, driven by a force he doesn't understand. In his effort to find out whether the strange person traveling with Trabuco is his sister, Carlo asks the peddler, "Who is that person - personcina - with you?"

"This strange word, Giorgio - `personcina' - what do you think it means?" They discuss the word, which in context is a trap. "How would you trick somebody with a word, Giorgio?" Zancanaro has no idea.

"Well, Giorgio, you could say it like this" Muti demonstrates with a slightly poisonous charm. "Or you could try it like this." This time Muti smiles, but his eyes flash with anger. "Or perhaps you could see what happens when you throw the word out." He shrugs and gives a staccato reading.

Zancanaro sings it the same way every time. Muti takes about an hour on the inn scene aria, "Son Pereda, son ricco d'onore." It's important to Muti that its three sections be fall of different colors yet form a link. "Giorgio, this man tells the story. He's making it up as he goes along, it's loose, and he is having a good time. You can play with the rhythm." Muti sings it as though it were a funny Schubert song, full of quirky color.

Zancanaro tries.

After several times through, Muti moves on to the middle section. "Giorgio, listen to this." Muti plays the accompaniment with fury.

"Yes. Maestro."

"But do you understand, Giorgio? This is a version of the destiny theme, the melody that starts the overture." Muti plays it. "Now listen." Muti plays the accompaniment again. It's obvious -- when it's pointed out. "What does that mean to you, Giorgio?" Not much, it seems. "You see," explains Muti, "this man is trapped, as are all the characters. They can't help themselves. They are good people - even this Carlo. He tells a story, it's fun, it's silly, then he is pulled the way the ocean pulls you into a violent storm. He forgets himself and becomes hate. Then all of a sudden --Giorgio, are you listening?"

"Yes, Maestro."

"All of a sudden he is this charming person again, telling this funny story."

Again, Zancanaro sings it the same way.

Finally, Muti sings it. He starts with an easy smile and absolute charm, savoring the swinging rhythm. Then suddenly, when the destiny theme erupts, his eyes cloud over, his face becomes fixed, every word is a dagger, and the final phrase is a vicious thrust. Muti - in character -- takes a short breath, laughs and shrugs, then returns to the jaunty tune, but this time, Carlo, as Muti sings him, can't quite lose the edge.

"You see, Giorgio, if you sing somewhat like that, you help the whole scene. That is the opera - the strange world. No one is what he seems. It is like Pirandello -- where is the mask and where is the real person? You remember Pirandello, Giorgio? And the chorus and Preziosilla and Trabuco and even Leonora offstage, you make them richer, for they can respond to you."

Zancanaro sings it exactly as he did the first time through.

"Well," Muti says later, "you have to understand singers. He is worried about his voice; he wonders if he will sing the first night. He likes Nucci and is worried about him, but of course he would like to sing the first night himself. And today they all have permanent jet lag. He will take a plane or drive to go on for somebody who is sick in Vienna or Graz or Palermo between these rehearsals, if he can. He'll sleep in the car on the way back - or not, if he can't find someone else to drive. And he will come to the rehearsals exhausted. And he is an old-timer. They learn it one way, and if you can get them to change two words, or add a color here and there, that is the most you expect."

Muti goes on to the convent scene. Everybody who can flees. Salazar runs out. There is a silence. She comes back in but clearly would rather be dead. Muti smiles at her and waves her closer. "Just try to feel it," he says. "You have a voice. But even if you are sick, if you feel and understand, that will help you sing." Once again he tries to get her to be Leonora. "Son giunta! Grazie, o Dio!" she yells.

"But, Ines, you didn't need to yell. If you believe in God, and this woman does, He is everywhere, right beside your mouth. And you are relieved. You have escaped your brother. "Son giunta - grazie, o Dio!" He sings like someone abandoning terror, almost without voice. And he looks around.

Salazar really tries, but she can't seem to get it. "You know why I looked around, what I was looking for?" She doesn't. "But Ines, what is her next line? 'Estremo asil quest'e per me' - this is my last refuge." Muti speaks to her in English and sometimes in Spanish. "I looked around for the cross, for the church, for death in life. You see, she would kill herself if she could. But she can't, because she believes. So here she can find peace - pace. And what will she implore God for later? Pace."

But Salazar, understandably, wants to get into the aria proper, which is treacherous. Muti tries to help. "I will relax the rhythm for you," he promises "Don't worry" When it comes to "Deh! non m'abbandonar," he says, "I will watch you and breathe with you. If you have a little trouble I will hurry and save you."

Salazar gets tighter and tighter; by the end of the aria she is so frightened she has to run out of the room again. Muti takes her hands and kisses her cheek when she comes back. Then he sings and acts Melitone, since even the third cover is sick. The entire character is there in his voice and face while he sits at the piano. The expression in his eyes changes on every word, as the priest, who is supposed to be kind, sneers at the stranger in need, then catches on that there may be scandal ("Scomunicato siete?") but is too dumb to see he's talking to a woman. Once again Muti catches the strange juxtaposition in the opera - it's funny and ugly.

The teenager with the beard stands up and sings. He is Antonio Papi, actually twenty-four, and is covering Guardiano. His is the first imposing voice I've heard during this trip to La Scala. Muti tries to give Papi and Salazar what acting teachers call an "inner metaphor.""Do you hear the flute here, signora?" he asks, playing the trill under "E questo il porto.""Your soul must wait for that and when you hear the trill, your soul must vibrate to it - you have found home, the blessing of God, light after the black night. Forget your voice. So you miss a note the flute is God's blessing."

"If she misses the note, forget the flute - it'll be the loggione whistling," wisecracks Zancanaro. All the men laugh except Muti. Salazar runs out of the room again.

"I could have been rude to Zancanaro," Muti says to me during a break. "But it was too late. And look, by now she better realize they may whistle. She must still be able to feel her part and give meaning. They even whistled Tebaldi here. If she is too scared to lose herself in Leonora, then it will be the story of Ines, not The Force of Destiny. I think you know which one is more interesting."

Still, when Salazar returns, he once again takes her hands and kisses her cheeks. He also sends everybody out but the round young man with the ponytail. Muti plays Alvaro's entrance, and this young fellow sings. Suddenly, an Italian tenor! His name is Salvatore Licitra (Cura's cover). Like Papi, he is someone Muti has found. Muti coaches him through every word and every phrase. "Don't let your voice slip back into your throat," he says. "Keep it forward. If you need a little time, I will wait for you. Don't start to bark." Licitra tries very hard and manages gorgeous phrases but makes mistakes. Muti is tender and infinitely patient. Later, Muti, will say, "Licitra had a great Italian voice in him but he didn't want to study and learn music, very few of them do, today, but he was a great loss." After a short period of great success, then some disappointment at his unevenness, Licitra died in a motor scooter accident in 2011 at the age of 43.

When Zancanaro is allowed back into the room, Muti inspires Licitra into singing "Or muoio tranquillo" with a long, liquid, large-scale, melting line that is really Verdi and really thrilling.

"Look," says Lauren Flanigan, "he is a great opera conductor. You have to be serious, and you have to work. But if he knows you mean it, he is with you every second. He breathes and sings with you. You know, while I studied him, he studied me. One day he said, 'California' -- that's what he called me after he'd asked me where I was from - `California, you can hold those notes a little more and take more time. It's in your voice, you can do it, and it will be great!' He saw things in me and potentials I didn't know were there."

"I don't know that anyone understands Muti entirely," says Bartoli, "but that is true of all great musicians, perhaps. He remembers everything you do. He has strong ideas, so he isn't always happy. But if you are on [the same wavelength] with him, he will help you be even better. He was at every rehearsal, even the staging ones, and he was always helping. And during the performance it was all in his eyes - the score, the feeling and his love for the music. It is hard not to give everything."

Later, I tell Muti most professional coaches don't do what he does, let alone conductors. Talk about the diaphragm, the tongue, keeping the voice forward, helping with breath? Impossible, in today's opera. Who knows that stuff? Perhaps worse, who cares?

"I will make a bet with you," Muti offers. "If you answer my question correctly, I will take you to the Four Seasons for lunch. If you cannot answer, you must spend a day without asking me any questions at all." I agree.

"Who was Maria Carbone?" I tell him. “I played for her for five years. Every day, I played for the singers she was teaching, and for those she was coaching and for her classes. There was nothing about voices she didn't know, and she taught me everything she knew. All the tricks and fakes - they can be useful - and all the muscles and what the tongue and the jaw do. And the exercises for them, and for the diaphragm. And how to sing on the words, to make the words your servants. They can even make your voice more beautiful. And now, I owe you a lunch."

"Io non amarlo? Tu ben sai s'io l'ami!"

This is the night of decision for Salazar. She is trying to sing Act I. But she can't manage any of the words clearly. "Sai" comes out as "soy," even when she repeats it for the third time.

"Ma! E sai! Non soy!" cries one of the power wives sitting in the theater. "Questo e La Scala. Non e una trattoria cinese!" (“This is La Scala, not a Chinese restaurant!!)

Muti stops after the act and talks intensely with his wife. He looks exhausted.

Cura has returned. So has Nucci. The tenor, in costume, marks. When he sings full voice, the throaty honking is alarming. He doesn't seem to know the role securely. The clarinet plays the solo to "La vita e inferno all'infelice" gloriously. Cura lets out his voice for the first and last time. He sings "I panteloni son troppo largo!" - the pants are too big.

Muti freezes. The maestros around me hiss. "Tenore!" cries one and makes the sign against the evil eye. Hugo de Ana and his costumer run up to the stage over the bridge. Muti starts again. Cura croons. Nucci, just out of the hospital, sings full out. When Cura falters and they have to take a section again, Muti asks Nucci not to sing. "No, Maestro, I will sing," he says. Cura mouths the words, Nucci sings full out.

The adjustments are made, and "Solenne in quest'ora" starts. The "wounded" Cura has been placed on strategically arranged pillows. Instead of singing, he starts tossing the pillows across the stage. Muti goes right on. In the "Sleale" duet, Cura tries his voice and cracks, so he just mouths the words.

The maestros around me are enraged, but Muti goes on. The camp scene is suddenly alive and stunning. There is wild energy. Muti sings Melitone's sermon from the pit (both Melitones are still sick) --hilarious and scary too. Luciana D'Intino also sings and acts full out, as does Ernesto Gavazzi, the Trabuco. Cura stands in the wings, fussing with his costume. Muti whips the orchestra and chorus up until the theater is shaking. "Maestro is truly incalzato tonight," says Arca to me. He means Muti is beside himself but putting it all in the music, and "Rataplan" is a fierce explosion. Those who usually yawn through rehearsals -- stagehands, tech people, covers - cheer at the end of this.

Muti throws his baton down and runs to his dressing room. The "suits" run after him. That fantastic chandelier comes on, and the applause continues. Leading it is Renata Tebaldi, who has been to all the rehearsals in the theater. She is radiant. "Look at the chandelier and the ceiling," she says. "This is my cradle, my temple! And you know, I would not be too unhappy if it were my grave."

(Tebaldi with epigone Aprile Millo, Madame Leyla Gencer)

Tebaldi has been ailing. I've been told she has been profoundly depressed. Muti has asked her to teach at La Scala's school. She has refused. He also asked her to come to all his rehearsals. At first she hesitated. He went to her house, and after interminable cups of coffee, he persuaded her to come.

Nucci passes us. She congratulates him on singing full out. "I'm old," he laughs, sarcastically. "I need to sing at my age. The young people don't have to."

I gossip (like everybody else) about the two Leonoras: one screams, the other can't begin to pronounce. "Have you no pity?" demands Tebaldi. "That poor creature is terrified. Let's pray for her." But at the same instant, we look across the theater. There is Salazar, evidently on the brink of tears, in intense conversation with Leyla Gencer.

"Uh-oh," sighs Tebaldi, "I have a feeling we are in for the other one the rest of this rehearsal." Muti comes and kisses Tebaldi's hands and her cheeks. She hugs him and pats his back. "You remember when we had tenors?" he asks Tebaldi. "Tucker, for example. I begged him to come to Italy more. He sang Pagliacci with me. I was green, and he was so prepared, he taught me. But when I told him at rehearsal he could hold a high note, he stood up and said, `Thank you, Maestro.' I told me, don’t stand up at a conductor, Tucker, he will think you want to kill him”.

He shakes his head. "I will go back over the camp scene and to the end of the opera. Licitra will sing Alvaro, Cura will watch. Lukacs will sing Leonora."

Our attention is drawn to Gencer and Salazar. One assumes Gencer is trying to be comforting, but it's not a quality that emanates from her. "That poor girl," says Tebaldi.

"She gave a great audition two years ago, and I worked with her. It was a wonderful voice," says Muti. "It is still a wonderful voice, Maestro," replies Tebaldi, "but she has done too many Toscas. She was a fine Donna Anna, and you know that is hard. But they must earn today, so they sing everything, and it is easy to growl and bark. That ruins your voice."

Gencer joins us and kisses and pats Muti. She kisses and pats me for good measure. "You are looking less well," she says. I admit I'm feeling unwell. "It will get worse," she says, "like the singing in this Fonza.""That girl needs to take six months off and breathe in the country air and not sing a note," says Tebaldi of Salazar, who looks very sad and vulnerable. "Then she needs to come back slowly, very slowly! No Toscas!"

"She needs to develop her falsetto!" says Gencer. "She needs to separate it from the rest of her voice and learn, so she always has the top. Then when she wants to use the chest, she can [do it] without the voice sounding like mud.""That is her problem, Leyla," says Tebaldi. "The chest - too high. This falsetto is a joke. A crutch!""It is how I made my career, Renata! I sing so many Forzas for so many years, I forget them. How many did you sing? I think you can remember."

Luckily, at this point, Arca comes to get Muti. Gencer hurls herself in front of him and kisses and pats him. I get Antonio Papi and introduce him to Tebaldi. He is wide-eyed and kisses both her hands.

"You are wonderful," she says. "You sound like the basses of my time."

Papi is almost crying. "I grew up listening to your records," he says. "I am very sorry I won't be able to sing with you."

She looks him up and down. "You know, I am very sorry not to be singing with you!" She throws her head back and her laugh resounds around the theater. He and I both see the irresistible and beautiful young woman she was. And we get a hint of that glorious voice.

Meanwhile, De Ana is sitting at the production desk, his head in his hands. "He saw me work with Lukacs, this afternoon. He knows!" he cries. He's talking about the staging rehearsals, which Muti watched like a hawk. De Ana will later be criticized for the singers' immobility. But at the rehearsal, De Ana was killing himself trying to get Lukacs to move and emote in the convent scene. He was literally running around the stage, begging her to do something -- anything. She just watched him, like an iceberg implacably heading for the Titanic. "I just told Maestro, she is like steel," grouses De Ana. "And you know what he said? `Good. She will need to be made of steel to survive this first night."'

The Metropolitan Opera does seven performances a week for thirty weeks. There were twenty-three operas in the repertory during the 1998-99 season. Some played six or seven times; some (Aida, La Boheme) twenty or more times. La Scala does ten to twelve operas a year, over ten months. Each plays six to eight times, alternating with ballets. A few that can be cast are brought back for three or four performances in the late spring or mid-fall.

Tickets at La Scala then were costly -- if you could get one. It is widely accepted by everyone in Milan that "ordinary people" cannot get tickets. "Bagarini" (scalpers) are pretty much the only way. They are used mainly by tourists. The box-office workers at La Scala are deliberately unhelpful.

By 1999 the Met, under Joseph Volpe, oddly enough also a despised leader, had become something of a model about how to function in a country that has no government subsidy. In 1999 the Italians at La Scala were studying Volpe’s massive fund-raising department. Of course, the Met does direct marketing, calling people at home. La Scala does none of that, nor does any other Italian theater. It is felt that they will have to. But this does not come naturally to arts executives who have grown up knowing about in fighting and intrigue politically as a way to get more money from the government but who are embarrassed about asking for money from wealthy people. And those wealthy people have no tradition of simply giving their money away. In the old days when the great families underwrote La Scala, they did so on a for profit and for power basis. “Here,” someone says to me, “you don’t get very far when you say give me a lot of money, and then go away quickly, you won’t get any of it back, and you won’t be able to control what happens at the opera house.” However in 1999 change is in the air. And the man who will try to bring this change about is Dottore Carlo Fontana.

"There are two words you should know in relation to Fontana," says one of his detractors - "Lottananza and buon salotto." The first refers to the system by which managers of arts institutions in Italy make their way up the ranks. It has its particularly Latin characteristics, but a similar club exists in all systems where there is heavy government subsidy. People (usually men) get into this system through political allies. Once they win their spurs, they are set for life. The buon salotto is sort of the old boys' club of Italy. These are the wealthy, the intricately connected, the all-powerful. Fontana belongs to both. "He was one of the best of that old school," says one of the young bloods at La Scala, who of course will not speak for attribution. "The question is, can he carry this theater into the future? It is an entirely different game. He doesn't know the rules."

"Yes,"Fontana barks, when I relay the remark. "It is a new game, and I have invented the rules!"

For a top-secret meeting of general managers from most of Europe's opera houses, hosted by La Scala in 1995, Fontana wrote an article (leaked to me by a disgruntled ex-employee), the first sentence of which read, "2001, opera addio." The article was titled "Poker d'Assi della Lirica" - poker with aces on the opera stage. It's a reference to the end of Aa II of La Fanciulla del West, when Minnie defeats her adversary with three aces. One assumes it was not lost on Dottore Fontana that she does so by cheating.

It was Fontana who pushed forward changes in funding methods but not even he could have foreseen the collapse of the European economy, the chaos in the Italian government or a measurable falling off of interest in the arts among Italians under 50. Our conversation in 1999 is no longer relevant and it may even be that Fontana was far from the worst of the Italian managers, even though I was told he rejected a fundraising project because he thought the director of it had “the evil eye”. I repeated this story to Fontana - a very youthful and handsome fifty. "Look, I let them do La Forza del Destino," says Fontana. "If we get through it with most of our fingers and toes, and only a few pets and great-grandparents die, we will be doing very well. And we have just hired a marketing consultant. Now, despite what my enemies say, I work. Good day."

PART TWO: Tebaldi, and the performance.

Since Sunday was mother's day I thought I would include the following bit of declamation from Cilea's opera L'Arlesiana. "To be a mother is Hell!!" (Esser un madre e'un inferno!!) As sung by Claudia Muzio.

.jpg)